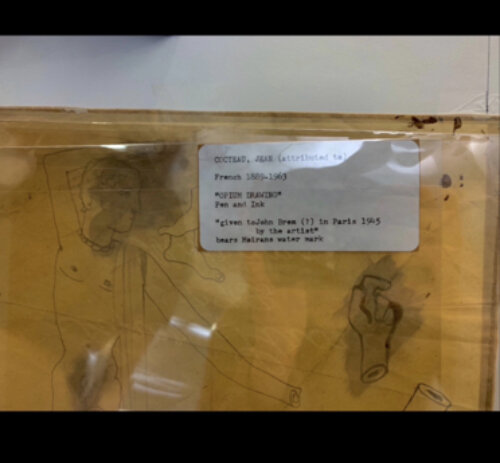

Entitled “Opium Drawing,” the work itself depicts a body, ambiguous as to gender, with its limbs strewn about the page and the head of a Grecian artifact. This object was most likely created by Jean Cocteau around 1945, as there is a note on the back of the image that this was given to a Mr. John Brem then. The image conveys an organic yet abstract aura, with the presence of small pen marks, seemingly half-thought in the production of this piece. Upon the piece, among the folds as though the artwork was kept in the pocket of the owner for a time, there are oxidized ink smudges working as a sort of covering for aspects of the body including the genitals, face and amputated hands. These smudges, although haphazard, bring another, perhaps inadvertent, meaning to the piece, as well as to the contextualization to be discussed in regard to Cocteau’s life and interests.

Personally, my fascination for this object lies within my attraction to the unpolished and obscure air, as many of the other pieces we had looked at in special collections did not present this very messy, off-the-cuff feeling and seemed much more curated and contemplative of their message. This is what draws me to believe, however, that this piece was in actuality some sort of reference for one of Cocteau’s other works or some sort of plan, as there is much depth to be found upon researching Cocteau and his fascination with bodies, gender, queering and androgyny. Further, I was also very interested in the smudges and crinkles this piece displays, as it gives not only texture to the piece, but also reinforces this very grimy and demented air.

Cocteau was famously known for his obsession with the male body throughout his work, as well as an interest in the misgendering of these corporeal depictions. Desilets discusses how within Cocteau’s film Orphée, which is an adaptation of Ovid's story of Orpheus from The Metamorphoses, Cocteau himself tried to distance this iteration of the play in attempt of an “aesthetic withdrawal from the world”(Desilets, 2012). Through this, it is a suggestion that this image was perhaps one of Cocteau’s storyboarding attempts for the film. Cocteau himself way a closeted gay who frequented opium dens after his initial exposure to the drug with Jacques Maritain. In this hallucinatory fit he thought himself among surrealist artists and made an effort take on this mode of art form, as it helped in his self-expression of his inner romantic emotions in an obscured and ambiguous fashion. Bancroft discusses Cocteau’s “Creative Crisis” after having taken opium for the first time, a concept which could possibly be helpful in the contextualization of this piece, as the title of the object is “Opium Drawing” and does present a sort of distraught tone, perhaps what one might illustrate in a time of crisis(Bancroft, 1971). Through this, Cocteau’s obsession with Ovid grew through his investment in gendered tales of antiquity and his attempt to subvert and redefine this classical tales through his art.

In further relation to Ovid, this image also seems to represent hermaphroditic conceptions of gender through the ambiguity and dismemberment of the body. Hermaphroditus as well, through his love of Salmacis, was joined forever to her as both man and woman in his hermaphroditic form. This piece, therefore, can exemplify a sort of hermaphroditism of sexuality for Cocteau and his internal conflict between acceptability and a sense of self. In the reference to Orpheus, this is somehow an illustration of his own condemnation of his homosexuality and his own internal manifestation of a Hermaphroditus-Orpheus mix. He, like Salmacis and Hermaphroditus,was too bound in his emotional queer-heterosexual paradigm, so hard to disentangle in the normative and disciplining context of 20th century Europe. Cocteau was a torn man through his love for Jacques and his need for a heterosexual, and legal gender performance. In relation to Orpheus, it too seemed as though Cocteau himself could not do anything to gain the love which he so ached for, but had to look forward through the fires of his emotion and continue on in hope that one day he would gain the love he hid. The combination of these two stories and their iterations through the eyes of Cocteau seem to be inspirations behind this piece, as they are a stratified concoction and historical rendering of Cocteau’s reality. Through the notion of this international and layered response to Ovid’s work, it is this which seems to represent the spirit of the Avant-garde, and the making of The Metamorphoses as avant-garde.

In respect to other avant-garde works, the piece was initially categorized within a collection of avant-garde dance-related works, assumedly by the position of the arms above the head of the body in the image. Initially, this piece and its connection to The Metamorphoses of Ovid elicits a connection to the iteration of The Metamorphoses through dance by Alvin Ailey. Further, the degendering and hermaphroditic connotations of the piece seem relevant to the Futurist movement, especially in the second wave to include women and the association with fascism which condemned homosexuality or contradictions of gender normative behavior. In relation to the history of Italian avant garde, this work reminds me of the work of Giannina Censi through the structures of her movement as well as the gender-ambiguous and futurist connotations of her work. There is a particular photo of Censi, attached below, which reminds me of “Opium Drawing” through the articulation of the arms as well as the interaction with a ball which could serve as the amputated limbs in Cocteau’s piece. Further, the work with shade and light in the photo of Censi can be related to Cocteau’s drawing and his use, inadvertent or intentional, of smears, shading, and speckling.

Other than the works of avant garde dance, this work may be analyzed in conjunction with the sort of bodily mutilation in the work of Marina Abramović.

Sources

Anderson, William S., ed. Ovid's Metamorphoses. University of Oklahoma Press, 1997.

Bancroft, David. "Cocteau's Creative Crisis, 1925-1929; Bremond, Chirico, and Proust." The French Review 45, no. 1 (1971): 9-19. Accessed April 21, 2020. www.jstor.org/stable/385687.

Desilets, Sean. "Cocteau's Female Orpheus." Literature/Film Quarterly 40, no. 4 (2012): 288-300. Accessed April 21, 2020. www.jstor.org/stable/43798843.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jean_Cocteau https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=pntMtN0fP38